Why transatlanticism can’t explain Trump’s peace talks

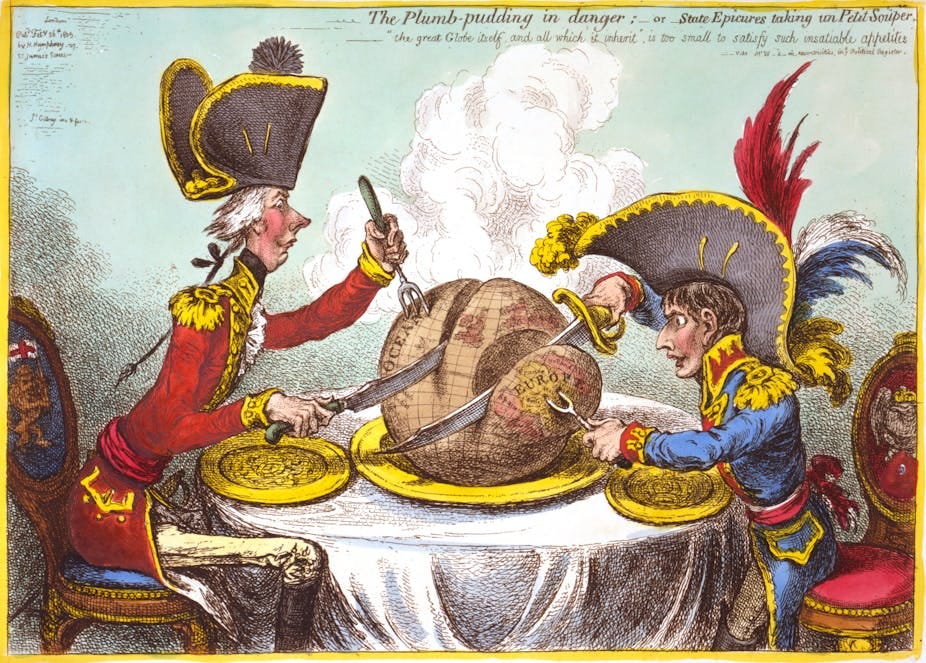

18th and 19th century imperial power politics is a better model

News outlets have largely turned Trump’s series of meeting on peace in Ukraine over the past week into yet another decisive “test” on the health of the transatlantic relationship.

Politico Europe wrote that “The transatlantic alliance survived a nerve-racking test on Monday,” while in an opinion in the Guardian, Rafael Behr wrote in a fun turn of phrase that “A flock of European pigeons raced to Washington… hoping to generate a fresh portion of transatlantic solidarity.”

While transatlanticism is a useful rhetorical frame — and it’s still very much alive, as I’ve argued elsewhere — it’s becoming an increasingly poor way to understand 21st century geopolitics, and Trump’s attempts to negotiate a peace agreement.

Instead, looking at the conflict and it’s possible conclusion through the lens of 18th and 19th century imperial power politics is a much more fruitful way to understand what’s going on — and how peace negotiations could conclude in the weeks and months to come.

This week I wrote a piece for The Parliament Magazine about European reactions to the Alaska summit and European leaders flocking to the White House. Historians and European officials I spoke with for the story stressed that Putin and Trump share an imperial approach to geopolitics that guides their negotiating style, and often leads to smaller European nations and the European Union itself being left out of the room.

“For both leaders, there is a strong idea that we should pursue politics like it has been done in the 19th century,” Martin Kohlrausch, a professor of modern European history at KU Leuven, told me for The Parliament. “The war in Ukraine has many features of an imperial and colonial war, of a bigger power extending its hold on territory as an imperial power projection.”

As examples, Kohlrausch pointed to Putin’s obvious affinity for 18th and 19th century imperial tsars, such as Peter the Great, who expanded Russia into the Baltic region. Ukraine also fits neatly into Putin’s larger colonialist vision for Russia. Ironically, Putin was also quick to highlight the Russian imperial connections with Alaska, saying during his speech immediately after the summit’s conclusion that many places in Alaska have Russian names. He also highlighted the long history of the Russian Orthodox Church in the state.

“For the last 30 years, we have fooled ourselves. We thought that Russia has changed and they don't have any kind of imperial aspirations, or we thought they can be dealt with in a dialogue, and so here we see what the results are.”

Peter Vermeersch, a professor of political studies at KU Leuven and a specialist in Eastern Europe, largely agreed.

“It’s important to keep in mind Putin’s own historical context, which is the greatness of Russia and the Russian Empire, and the lost Soviet Union,” he told me, again for The Parliament. “If there’s one consistent element to what drives Putin, it’s his own take on history, and how he believes Russia should move from a pariah state to a world power.”

A member of the Estonian parliament I spoke with doubled-down on the thinking that imperial aspirations were pivotal to understanding Putin’s war in Ukraine — and why that matters so much for the rest of the European continent.

“For the last 30 years, we have fooled ourselves,” he told me. “We thought that Russia has changed and they don't have any kind of imperial aspirations, or we thought they can be dealt with in a dialogue, and so here we see what the results are.”

Historians and scholars such as Timothy Snyder have long highlighted the importance of understanding Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as a war rooted in imperial and colonial ambitions. This is by no means a new idea.

However, it’s becoming increasingly clear that Trump largely plays by a similar playbook when it comes to geopolitics. He sees and treats Putin as a fellow sphere-of-influence leader, as his red carpet treatment in Alaska showed. That imperial approach — not any vestiges of transatlanticism — informs his approach to the negotiating process.

Since the beginning of his second term, Trump has voiced interest in American control over Greenland and the Panama Canal. He’s celebrated President William McKinley, who oversaw a period of American expansionism during the Spanish-American War, and has veered towards a geopolitical negotiating stance that includes face to face meetings between those who “have the cards.”

The Alaska summit, in which he met directly with Putin over the head of Ukrainian and European leaders, is a grade-A example of his individualistic, realpolitik stance. His long-held derision for the European Union — which lacks a hierarchical executive in the model of imperial powers like the United States, Russia, or China — is another.

The great-power bargaining approach to geopolitics is leaps and bounds from the purported rules-based international order of post-war transatlanticism, in which (at least on the surface) Europe, United States, and Canada worked together with aligned geopolitical goals.

Transatlanticism still makes sense as a concept to understand pivotal flows of people, goods, and services that define the day-to-day lives of the 1 billion people living on both sides of the Atlantic.

However, it’s become an outdated concept by which to understand Trump’s approach to ending Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Instead, Trump’s series of summits shows that in the realm of international politics, the age of U.S.-led transatlanticism is in the process of giving way to something older and far more dangerous — great power imperialism.

I am no expert whatsoever, but yes, the things you are saying sound right. Obviously, countries like Hungary are a big problem when it comes to efforts at EU unity. So rewriting the EU laws to allow the majority to make the decision seems to make sense. As for the unity they demonstrated at the White House this weekend, it's good that Ukraine and the EU showed some solidarity. But did it move the dial at all? Some writers, like Mark Landler, in the New York Times this morning, seem to think it didn't. In the end, Ukraine and the EU may need to look to Asia and Africa for support, if the USA is unwilling to provide enough of it.

This sounds right on target. Timothy Snyder is one among many writers and historians who’ve been making this point. So where does this leave Ukraine and Europe? How will they deal with it?